By Agricompas Crop Model Team

In recent decades, agriculture has been under the scrutiny of society and the scientific community due to the negative impact that it generates on the environment. These impacts are of many types, including deforestation, eutrophication of water bodies, the reduction of biodiversity due to the intense use of pesticides, and the emission of greenhouse gases (GHG).

In relation to GHG emissions, these are released in the process of manufacturing inputs, such as, fertilizers. Also included are the GHGs released as a result of the transport process: first of inputs towards the production areas, and then of the product towards the consumption areas.

A Complicated Task

But the most complicated task from a methodological point of view is to determine the GHGs that are released during the production stage. Among the GHGs released to the atmosphere during the production phase, the most important are carbon dioxide, methane (in systems where the soil is in anaerobic conditions), nitrous oxide, and ammonia.

Methodological difficulties are associated with the fact that these emissions are determined by dynamic factors such as climate, soil characteristics, and management practices, especially fertilization and irrigation.

Since it is impossible to survive without agriculture, efforts have focused on developing and implementing production systems able to maximize yields while reducing negative effects on the environment. A prerequisite for advancing in this direction is to measure the GHGs generated during agricultural production cycles.

Static Chambers

To understand better the methodological challenges involved in determining these gases under field conditions, let us take methane as an example. This gas is generated as a product of the decomposition of organic matter in the soil under non-oxygen conditions, typical of crops such as flooded rice.

Traditionally, static dark chambers have been used to collect samples that are later analysed by the gas chromatography technique in specialized laboratories.

This technique has a high sensitivity to determine low methane fluxes, is easy to handle, and has a low cost. But its main disadvantages are related to the low spatial representativeness and the inability to generate data at different time scales.

In other words, the measurements only represent the gas flux in a small area and at a specific time point, which leads to the question: can this technique generate data to represent what happens in inherently heterogeneous and dynamic agricultural systems?

Eddy Covariance

It is in this context that the technique of eddy covariance appears, as an alternative way to measure, among other variables, methane flows with greater spatial and temporal representativeness.

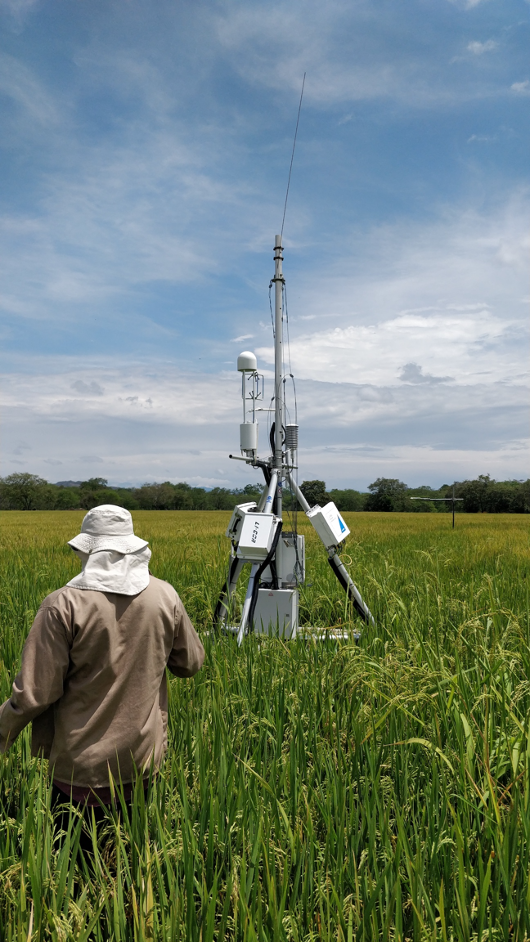

This technique employs a complex assembly of sensors arranged in a tower (which is why they are usually called eddy covariance towers) that records variables that ultimately allow the determination of the exchange of gases and energy between the crop and the atmosphere.

Although the foundations of the technique and data processing are complex, it provides useful information in the search for more sustainable agricultural systems.

This is because, in addition to determining GHG emissions, such as methane and carbon dioxide, the eddy covariance technique also provides information about the flow of energy between the soil, the plant, and the atmosphere. This means that information is also useful to improve the water use efficiency since the measurements allow the determination of water fluxes from the crops to the atmosphere (evapotranspiration).

All of this information is comparable in terms of accuracy with data obtained by reference instruments such as lysimeters. Therefore, the technique of eddy covariance is currently a powerful ally in the search for more sustainable agricultural systems.

Use with EcoProMIS

The EcoProMIS project has four eddy covariance towers in Colombia, two recording data on rice crops, and two on oil palm crops. The data collected by these stations are being processed to calibrate crop models that allow, in addition to predicting yields, to estimate GHG emissions.

Together with our partners (CIAT, Cenipalma, Fedearroz, IWCO, Pixalytics and Solidaridad), the final objective of the project is to generate “knowledge and decision support” to orient stakeholders towards sustainability.